The Buckeye Trail: Still Just an Idea

“The Buckeye Trail: Still Just an Idea…”

A selection of passages from the 1958 article “So Far It Is Just an Idea” with contemporary commentary by Hannah Griswold and Evan DeCarlo of the Ohio Field School.

Key

PC: Perry Cole, Author of the Original Article “So Far It Is Just an Idea” (1958).

HG: Hannah Griswold, Ohio Field School Researcher (2020).

EPD: E.P. DeCarlo, Ohio Field School Researcher (2020).

In early March of 2020, just before the full outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic in the continental United States and subsequent national state of emergency, Hannah Griswold and I were engaged in a week’s worth of ethnographic fieldwork on behalf of the Ohio Field School – a workshop operated by OSU’s Center for Folklore Studies. The projects of the 2020 OFS student pairs (6 pairs in total) were multifarious, each group working with a separate “community partner” – local nonprofit organizations operating in Perry County of southeastern Ohio. The project Hannah and I elected to take on consisted of a week embedded with the Buckeye Trail Association at their headquarters in Shawnee – a village of around 700 residents along the tree line of Wayne National Forest.

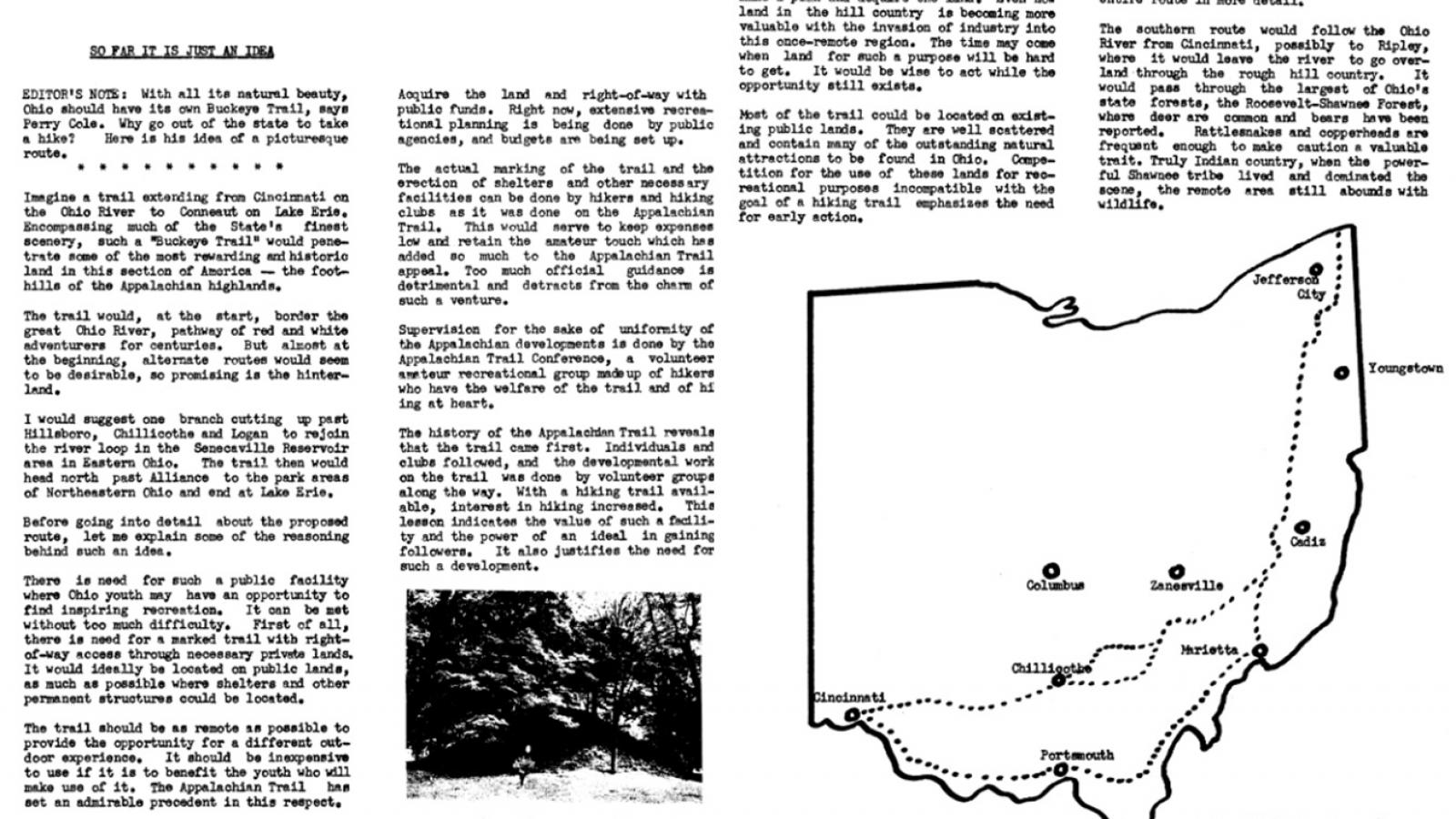

The Buckeye Trail is a 1,400+ mile trail that forms a loop around the interior borders of the state of Ohio. Formed in 1958, both the physical trail and its network of workers and volunteers have been growing and changing for well over half a century. On paper, the project I was to be tackling with Hannah was the digitization of the files of one of the BTA’s late founding members: Merle H. Marietta. This box of old papers, booklets, and mimeographs served as a kind of time capsule, a long distant perspective on the earliest years of the Buckeye Trail’s inception and development. But we soon realized, as we started the slow process of copying the old papers in a tiny corner of the BTA’s office, that this scanning project was to prove only a small part of our much larger dive into the history and present day picture of the Buckeye Trail – both its physical and social shapes.

Andrew Bashaw, the executive director of the BTA, was to serve as our principle guide along this journey along with Richard Lutz, the BTA’s GIS coordinator and chair of the trail management team. Each has what is called a “trail name” – an earned title used only when out blazing or hiking. Andrew’s is “Quickdraw Bashaw” and Richard’s is “GIS Trailblazer.” At the outset of our project, Mr. Bashaw had asked of us to consider the Buckeye Trail from the perspective of one of its most important founding documents, a 1958 Columbus Dispatch article by Perry Cole entitled “So Far It Is Just an Idea.” The article served as a kind of proposal for the construction of the Buckeye Trail, emphasizing not only the geographic shape of the trail but also the various social and cultural benefits the state of Ohio might reap from its (then) possible blazing.

In considering what form our final public facing project for the Ohio Field School would take, Hannah and I agreed that it would be most meaningful to end where we had begun: with the very same article. Thus, our ultimate project. Below are a selection of passages from the 1958 “So Far It Is Just an Idea” presented as though they are “in conversation” with present day accounts of some of the same ideas and themes as documented by Hannah Griswold and myself during our week with the Buckeye Trail Association.

PC (1958): “The trail should be as remote as possible to provide the opportunity for a different outdoor experience. It should be inexpensive to use if it is to benefit the youth who will make use of it. The Appalachian Trail has set an admirable precedent in this respect […] The actual making of the trail and the erection of shelters and other necessary facilities can be done by hikers and hiking clubs as it was done on the Appalachian Trail. This would serve to keep expenses low and retain the amateur touch which has added so much to the Appalachian Trail appeal. Too much official guidance is detrimental and detracts from the charm of such a venture.”

EPD (2020): Much of the Buckeye Trail’s image, both historical and contemporary, is bound up in a sense of scale – especially scale in relation to the Appalachian Trail. There is no doubt, many of the BTA members affirm, that the Appalachian Trail is the better known (and certainly longer) of the two, functionally serving as an international icon and standard. And while the frequent discussion of the Appalachian Trail in both the modern-day BTA headquarters and even the files of the late Merle H. Marietta may seem envious in nature, a closer perspective reveals not envy but the kind of tempered aspiration that allows for a distinguished sense of self, for a picture of the Buckeye Trail that is inspired by – but entirely unique from – the shape and purpose of the Appalachian Trail; the BT’s mission, after all, is about Ohio.

Nevertheless, Ohio is a big place – and only one place part of a much bigger place, itself made up by many smaller places… ad infinitum – and so both the Buckeye Trail and the BTA are always caught up in a constant sense of shifting scales. On our first physical outing along the Buckeye Trail, Richard Lutz (GIS Coordinator and Trail Management Team Chair – pictured above) points to a fork in the path and tells us “From here, one can choose to walk around the state, to walk to California, to Delaware, even to follow Lewis and Clark‘s original route across the country].” It’s something that’s difficult to conceive of -- a circular, entirely enclosed trail seems thoroughly local in nature (at least next to something like the Appalachian Trail) – and yet the BT is not only comprised of a network of trails itself, but also sits at the nexus of many dozens of other trails whose various purviews span areas as wide as the North American continent itself.

When we interviewed Andrew Bashaw, the Buckeye Trail Association’s Executive Director (pictured to the right), he spoke some of this sense of scale when asked what the ultimate objective of the trail ought to be -- in this case, the scale toed the linebetween the individual and his history, the idea and its history, and of course the thing itself. “Objectives should be measurable,” he answered. “A state of being is the real goal, but how do you measure that? Setting concrete quotas can sometimes be unreasonable – so we had to find reasonable ways to set goals for ourselves like finishing the remaining trails and, ultimately, moving them off the roads and into safe corridors.” He paused, then, thought some, and said suddenly, “Some people are obsessed with the idea of an ‘official’ trail. I’m less interested in that – there’s a lot of nuance that comes up when you get as deep into it as I have. The rules are rarely absolute. You have to take a step back. Our primary interest is in it [the BT] as a hiking trail – but so many have other kinds of adventures in mind – the history is on that trail and that’s what’s important; it matters a lot less how you get there. It’s a corridor for all sorts of adventures, but history and ideals are what make the Buckeye Trail important. Every inch has a story that another hiking trail might not. It becomes part of peoples’ stories when they walk it – the histories of individuals are conjoined with bigger histories by hiking this trail.”

PC (1958): “This could be the skeleton of the Buckeye Trail. Actually it should be as endless and as boundless as the energy and the imagination of those who would use it.”

HG (2020): The Buckeye Trail isn’t done. The Buckeye Trail will never be done. This is because the trail goes beyond the 1,400+ miles of paths that comprise it. The trail is carefully constructed and reconstructed every day by those who plan it, build it, and travel on it. While Evan and I were in Shawnee, I walked on the trail several times. The first time I walked on the trail, I soaked up some moonlight and took a moment for quiet reflection. The trail was peaceful and very muddy, but that was all I knew about it. By the end of the week spent learning and working with the Buckeye Trail Association and the dedicated volunteers of the Buckeye Trail, my perspective began to shift. As I walked the same section of the trail near Burr Oak State Park, I found that it was louder now, sound bytes of our interviews played in my head when I looked at the path. Almost everyone we had talked to had walked this particular section of the trail, but even if they hadn’t, each footstep connected me around the entire trail both past and present. For Connie Pond (pictured

right), a former president and current secretary of the of the Buckeye Trail Association and co-author of the guidebook Follow the Blue Blazes, the trail is animated by the relationships and effort it took to make the trail. For example, she describes how walking the trail between Johnson Farms to Lockington feels different than walking just walking around Johnson Farms. She says, “It’s a short hike, but I know the struggles the BT people went through to get that trail there, to get it manned… So there’s just knowing – I know more about that trail.”

As echoed throughout the week, it doesn’t matter where you are on the Buckeye Trail – if you just keep walking you can eventually get right back to where you stand. The sentiment is quite powerful and animates the entire trail as one, even across time. The Buckeye Trail has only been around since it was “just an idea” in 1958, and many parts of that original trail no longer exist or have changed. The trail is constantly building and reliving its own history while allowing those who spend time on it to feel more immersed in the history of the state at large. The trail invokes and offers a sense of history that can even trace back farther than its own. For example, Jeffery Yoest (pictured above), a longtime volunteer of the Buckeye Trail who has recently projected to section hike the entire trail, explains about traveling through the canal corridors, “You're walking along these trails, and you're in the middle of nowhere, and my imagination goes back to 150 years. 150 years. I'm here by myself; I haven't seen anybody for an hour. I'm walking along this towpath. There's nobody here... 150 years ago, there would have been canal boats going up and down here.” For me, the Buckeye Trail seemed to warp time. As I was helping to reroute some trail in Wayne National Forest to be offroad, I simultaneously learned about the history of extractive industry in the area (which is still physically notable in the gob and slag laying about the trail) and constructed a trail that has never been seen before.

PC (1958): “The history of the Appalachian Trail reveals that the trail came first. Individuals and clubs followed, and the developmental work on the trail was done by volunteer groups along the way. With a hiking trail available, interest in hiking increased. This lesson indicates the value of such a facility and the power of an ideal in gaining followers. It also justifies the need for such a development.”

HG (2020): Today the Buckeye Trail recruits more than just hikers. Andrew Bashaw made it clear that you can travel the Buckeye Trail in almost any way you desire. For example, while you cannot kayak the entire Buckeye Trail loop, Bashaw is quick to stress that there are parts of the trail where this is accessible. There are also parts of the trail where you can bike, horseback ride, or drive, and various other activities. Jeffery Yoest was quick to point out how the Buckeye Trail is full of potential when he said, “You can find anything you want on the Buckeye Trail.” Furthermore, the mission of the Buckeye Trail to have and maintain a trail that loops around all of Ohio, is held in the hearts of the volunteers of the Buckeye Trail, including those who do not hike or do not consider themselves hikers. The structure of the Buckeye Trail Association creates a network where a volunteer of various skill sets and interests can involve themselves in the maintenance of the trail. At trail level, this can include attending work parties where teams of volunteers spend a day or several days out building the trail, bonding nightly over campfires. Work parties often include the need for someone to volunteer to cook meals for the Chuckwagon, a meal cart built by Buckeye Trail volunteer and coordinator of the Run For the Blue Blazes, Herb Hulls. Volunteers can also choose to become trail “adopters” or maintainers, which is a slightly different type of commitment to trail building. Maintainers are responsible for keeping up the conditions of specific stretches of trail. Then there are roles that are not directly on the trail. For example, volunteers can join a board or a committee. Jeffery Yoest, who is part of a nominating committee responsible for finding and nominating candidates for the board elections that happen at trail fest, says that to serve on a committee one only needs “the desire to help the organization and willingness to donate your time and efforts.” He also says that whether or not committee members hike on the trail often they are all dedicated to the cause and “contribute in great ways by all the needs that the Buckeye Trail has in terms of the organization, making it run.” While for the Appalachian Trail the “trail came first,” the Buckeye Trail is co-constructed by the actual needs of the physical trail and the human relationships that it fosters.

EPD (2020): That the Buckeye Trail should be known, even before its physical inception, as an undertaking which would come to rely upon and consistently be inspired by acts of volunteerism speaks not only to the prescience of the trails’ founders, but also to the reality (as so often evinced by the example of the Appalachian Trail) they knew they ultimately faced. As so many of our informants over our week with the BTA noted, a trail is built by walking on it. For those intimately familiar with trails -- their construction, maintenance, and use -- there seems to be no higher truth than this fact. And that walking, for the BTA, takes shape multifariously -- hikers, blazers, trail maintenance crews -- these all constitute acts of volunteerism. Bashaw said, “so many heroes and heroines of the BTA have official positions that don’t nearly sum up all the things they do … They are the people who raise their hands no matter what. It’s a blessing, it’s beautiful, but it gets confusing.” Some of these volunteers have been working with the BTA for decades longer than Andrew himself – he started in 2010 after a four year tenure with the North Country Trail Association. “It’s hard to tell who is who's boss, sometimes!” But these forever volunteers, Andrew says, are what makes the BTA so unique. “They’re mostly pretty terrible at logging their hours,” he tells us wryly. “That’s just not what’s important to them… 1,200 members in total, and 10% of them are volunteers. That blows every other nonprofit out of the water. And 400 of them donate regularly. That’s also completely amazing and unusual."

PC (1958): “In these times so reminiscent of the ‘Roaring Twenties’, youth should be encouraged to slow down and learn to know their native land. They need the invitation for a back-to-nature movement, for the opportunity to form real, sound friendships. Such an experience could do much to help youth retain or restore a proper sense of values.”

EPD (2020): This kind of rhetoric marks much of Cole’s original piece -- the call for the (then) possible Buckeye Trail seems strongest when it is made on behalf of Ohio’s youth. It is difficult, though, to think today of the young people of the 1950s as needing to “slow down.” In our modern myopia, we imagine that anyone growing up nearly 70 years ago must have lived a positively bucolic bumpkin life when compared to this, our rapidly evolving information age. But the bald-faced fact of the matter is that this kind of talk really has a lot less to do with any particular era than it does with the the relationship between age-groups; it’s a universal fact that, whether for better or worse, senior generations across history have always found some way to urge their juniors to “slow down” and seek out that “proper sense of values.” In the United States, that urging frequently takes the shape of a call for a return “back-to-nature,” as Cole allows. It’s certainly a nostalgic call.

Andrew Bashaw, when telling us of his childhood in rural Ohio, said, “Every morning the door was opened and my siblings and I roamed free all day only to return for dinner. It was an idyllic setting – acres and acres of cornfields and forests. We all used to search for flint arrowheads and the like.” Later, he told us he had always been enchanted with the idea of “getting paid to walk around the woods… to be a naturalist.” Many of the BTA’s most prominent members share this nostalgia for a different time -- idyllic, perhaps, as Andrew puts it -- when the young spent their time outdoors. Herb Hulls (pictured right), for instance, one of the BTA’s oldest members (both physically and in terms of tenure) even spent a great deal of his youth (a period he calls “young and dumb”) riding roughstock in the rodeo and then cowboying in Montana after his military service -- and all well before he had ever even heard of the Buckeye Trail. Today, despite his age, Herb can still be found out working the trails; many of his juniors shared with us that they have difficulty keeping up with the old cowboy.

As we consider this original article -- and the BT’s concomitant evolution from idea to reality (but, as we posit, most importantly still an idea) the ultimate trajectory of this original call for a “back-to-nature” approach is difficult to measure. As Andrew Bashaw shared with us, it’s a tricky thing to figure out just who exactly (in this case, what demographics) is out there walking the Buckeye Trail. One might be forgiven for guessing that the youth have little to do with things -- that perhaps Cole’s original idea has not played out in quite the way he imagined; after all, the majority of individuals we interviewed were at least middle-aged, many of them seniors. The general population demographics of Shawnee, OH (where the BTA is headquartered) did not help this image much. It wasn’t until one of our final interviews that I learned just what exactly the Buckeye Trail can and does mean to some of the contemporary youths of Ohio -- and just how much speed really can be involved in “slowing down.”

On our last afternoon at the Buckeye Trail Association, Hannah and I interviewed Everett Brandt and Kevin Morissey. We had been hearing about these two all week -- even the BTA’s most senior members spoke of them with a kind of awe. Brandt is the current record holder for the fastest thru-hike of the Buckeye Trail. While not exactly a teenager, we believe (as, it seems, does the BTA at large) that his endeavor counts as not only youthful in nature, but as a true embodiment of Cole’s original call to action. Brandt trekked for miles and miles around Ohio (over 1,400!), sometimes hiking, sometimes jogging -- sometimes in the woods, sometimes on the road (as Andrew Bashaw and many other BTA members frequently noted to us, one of the BTA’s top current priorities is to move the entire trail off road). Kevin Morrisey accompanied Brandt through several sections of this thru-hike, filming him as he went; the two plan to soon release a documentary about the project. Most interestingly, when we asked Brandt why he had done something so challenging, what he told us surprised me a great deal. Naturally I’d assume his reasons were off the thrill-seeking ilk -- and, while thrill-seeking may have played a part, Brandt admitted to us that his trip was made on behalf of the Buckeye Trail’s national image. Before the hike, he had been working with the BTA for some time, helping to maintain trails as many members do. It wasn’t until he discovered that the Buckeye Trail was listed on a popular hiking record time site (Fastest Known Times) but had no accompanying record posted that he decided to make the journey. He did it to help inform the people of Ohio about their state’s “best secret” by sticking a record onto it.

When I asked him why he thought (along with many BTA members) that so few Ohio residents seemed to know about the trail, Morrisey answered. “People think about trails in sections, in localities,” he told us. “It’s less common to think (or know) about the whole thing. But it’s important that people do.” Without fail, this was the kind of spirit Hannah and I encountered no matter who we encountered during our time embedded with the BTA: a profound sense of duty to Ohio – even if that duty might lead to a lot of toil in obscurity. One is reminded, finally, of Jean Giono’s seminal short story “The Man Who Planted Trees” -- the story of a single man restoring a wasteland back to verdance and ecological good health. When the land is so restored, villagers come to live in the shade of the new trees that have been planted, blissfully unaware of all the labor that has gone into their nourishment over decades of solitary work. Giono writes:

“He was an athlete of God… This had all sprung from the hands and from the soul of this one man - without technical aids … [It] struck me that men could be as effective as God in domains other than destruction … When I consider that a single man, relying only on his own simple physical and moral resources, was able to transform a desert into this land of Canaan, I am convinced that despite everything, the human condition is truly admirable. But when I take into account the constancy, the greatness of soul, and the selfless dedication that was needed to bring about this transformation, I am filled with an immenserespect for this [man] who knew how to bring about a work worthy of God.”

I cannot help but to think of this as I sit reflecting on our time with the BTA. The volunteers and workers there seem touched with the same sort of sense: that their mission is one worth doing -- even as it bears fruit invisibly, even as it helps in silence, possibly unknown to those to whom it brings joy. “So many times people will be walking on the Buckeye Trail and never even know it,” Andrew Bashaw told us often. And never once did this seem to bother him. Certainly the BTA is engaged in publicity of all kinds -- getting the word out is as important to them in this age of social media as ever -- but never once did Andrew Bashaw seem troubled by the idea of enthusiastic boots enjoying the Buckeye Trail, the very thing to which he has dedicated his life -- whether those boots knew it or not. In this sense, I am left with just such a lasting impression of the BTA members and all that they do -- that they truly are among “God’s athletes.”

The trail was just an idea when it began -- and, so long as it serves in this way, it will remain just an idea. And there’s a real beauty in that.

Read Ohio Field School fieldworker Evan DeCarlo's essay, "Placemaking and the Blue Blazes: The Ohio Field School Comes to the BTA" in the summer 2020 issue of Trailblazer, the quarterly publication of the Buckeye Trail Association.