Monday Creek Restoration Project

The Source of Monday Creek

The beginning of a creek is its source, the beginning of the Monday Creek Restoration Project (MCRP) is one of struggles and one of triumph; one of future and one of past; one of individuals and one of community. When the MCRP began there were only four species of fish alive in the creek, due to pollution from acid mine drainage. Now, years later, the creek supports thirty-seven fish species. While the future of Monday Creek has never been brighter, it is also important to remember where it started. The history of the project can be told through the individuals who had been there since the early years. Some of these individuals sat down with us and told us about their work with MCRP. The photos and interviews we collected during our time with them allow us to share their stories.

History of the Monday Creek Restoration Project:

Creating a Nonprofit

An important piece of legislation was the Clean Water Act of 1972. This act was passed with the goal of restoring, improving, and maintaining the United States’ water. In 1987, an amendment was added to the Clean Water act that created, under section 319, funding to clean pollution from nonpoint sources, this funding would be known as 319 grants and would be administered by the United States’ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Many of the early watershed projects were funded through these 319 grants. Meanwhile, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) began to fund water quality specialist for special cases in watersheds that had large amounts of restoration work to be done, such as Monday Creek.

The Ohio EPA provided money from the U.S. EPA for different watershed projects throughout the State of Ohio using those 319 water quality grants. Smaller grants came from agencies such as the Office of Surface Mining, Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), and the Forest Service.

Rural Action was also an important part of MCRP’s restoration. Rural Action’s mission is to create sustainable asset-based community development. To help achieve this goal, MCRP was created as a project of Rural Action’s Watershed Restoration Project (now called the Watershed Program). Rural Action viewed Monday Creek as an opportunity to create a foundation of sustainability in the community through clean water and watersheds. After the success in Monday Creek, Rural Action continued and continues to work in other watersheds. Current MCRP AmeriCorps, Ricky Vandegrift said that, “The type of work that Rural Action and Monday Creek that were doing, it tends to be something that’s close to a lot of people’s hearts, in one way or another. So, you know, it kind of calls them to action eventually.” This call to action can be seen through the many workers and volunteers that helped start MCRP and contributed to its success.

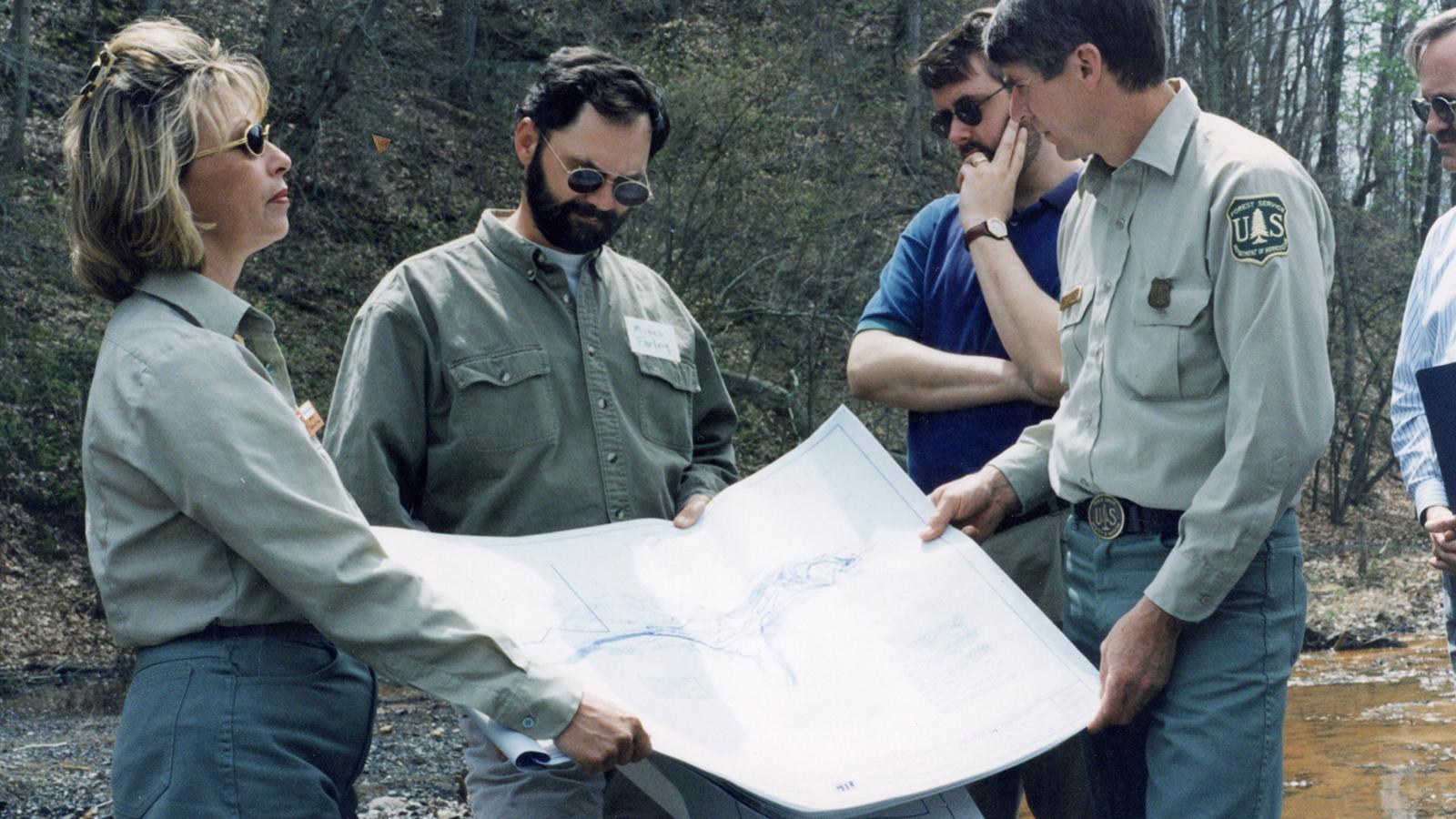

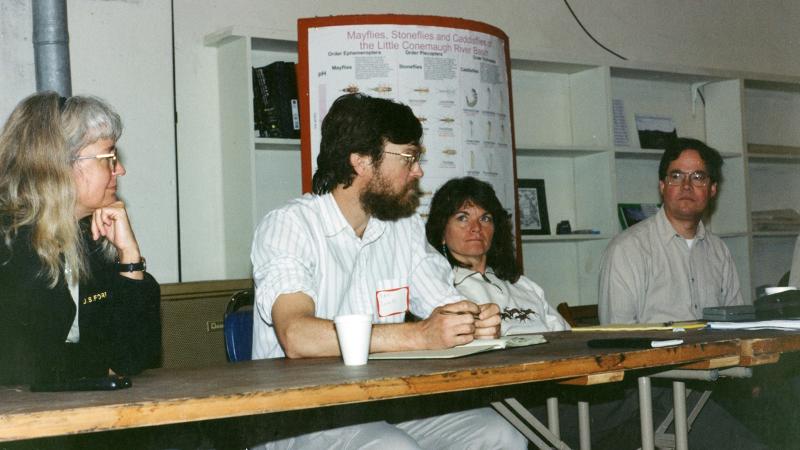

The formation of the Monday Creek Restoration Project can be traced back to Doctor Mary Stoertz, a professor of hydrogeology at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio and Mary Ann Borch, a VISTA for Rural Action. These two approached Mitch Farley, who worked for ODNR, about the idea of creating a watershed group of interested citizens to do a restoration project. Several different watersheds were considered, such as Sunday Creek and Raccoon Creek, before Monday Creek was chosen. The watershed group started small but over time and through hard work, grant money began flowing in that allowed them to begin to study the watershed, and using this knowledge, decide which sources were most important for reclamation and carrying out those reclamation projects. The group grew to include several important members such as Marsha Wikle from the Forest Service, Dan Imhoff from the Ohio EPA, Mike Steinmaus, and others.

The first watershed coordinator for MCRP was Mary Ann Borch who started in that role in 1994. Mary Ann was originally an AmeriCorps VISTA for Rural Action before assuming the role of coordinator. She ran the MCRP out of her home with the help of VISTA volunteers. Mary Ann left Monday Creek after accepting a position with ODNR.

In 1999 a new watershed coordinator was chosen, Mike Steinmaus. Mike had recently moved out to Ohio from Iowa, as his wife had begun working as the community development director for Rural Action. Along with a new coordinator, MCRP also moved into its current office in New Straitsville. When he first started, Mike only had one other person working with him, an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer named Norah Newberg, who had previously worked with Mary Ann. Her help was crucial as she was able to show the area and the watershed to Mike and she remained a part of the MCRP staff at the conclusion of her term.

Growing with a Little Help

Restoring an entire watershed honeycombed with abandoned mines, like the Monday Creek watershed, is an enormous task. In addition to the grant dollars, watershed restoration demands sizeable amounts of labor as well as specialized tools for water quality monitoring. Fortunately, MCRP had plenty of help. As written above, ODNR funded much of the labor driving watershed restoration in Monday Creek. But there were other channels of support as well. As Mike Steinmaus recounted about the Forest Service, “… we [MCRP] didn’t have any ‘tools,’ we didn’t have any pygmy meters, anything to measure the creek. They [the Forest Service] did. We’d use their equipment.” Not only did the Forest Service allow the organization to borrow tools, but also allowed them to use Forest Service trucks for traveling around the watershed. According to Dan Imhoff, the Ohio EPA lent tools like these as well.

In addition to this resource sharing, members of agencies like the Forest Service, Ohio EPA, and ODNR lent labor-hours to support water quality and biological sampling, training, decision-making, and many other tasks integral to MCRP’s operations. As Mike told us, it was not just himself and MCRP’s AmeriCorps VISTAs making decisions about how to restore the watershed—people from multiple agencies were all involved in the decision-making processes that drove restoration efforts. Mitch Farley, of the ODNR, told us, “Dan [Imhoff] and others [like] Kelly Capuzzi [of the Ohio EPA] were there all along the way, providing assistance with, you know, their ideas and helping to organize water quality sampling.” Mitch himself was there all along the way as well. This ethic of resource- and labor-sharing helped create the conditions that made the restoration of and care for Monday Creek possible.

Making the Creek a Place

Discussing his work with the Ohio EPA, Dan told us, “… we thought we should start working on the watershed model, rather than on artificial political boundaries.” A watershed crosses these political boundaries and thereby confounds efforts to manage it through typical state-designed channels. The shift to a watershed-based model reconciled the divide between environmental restoration and things-as-they-are. The work done by the watershed group that resulted from this shift did a lot of good work restoring the stream. As recounted above, when Mike Steinmaus started at MCRP in 1999 Monday Creek had four species of fish, and when he left there were twenty-four (today there are thirty-seven). Not only was this restoration success good for the ecology of this particular part of Appalachian Ohio, it was good for the narratives about it. Mike told us that in the 1990’s the Ohio EPA had pronounced Monday Creek a “dead stream.” He continued, “they came out and said there is nothing that can be done about it, just leave it be.” In yet another respect, Appalachian Ohio had been disregarded and undervalued. MCRP’s work helped to reverse this trend of neglect, at least in one respect, and continues to do so.

Yet, it often takes more than ecological restoration to restore a place. A community’s stories and interactions with the watershed are what make it a place. Kylee Nichols and Ricky Vandegrift, MCRP’s current MCRP AmeriCorps, both affirmed the importance of these kinds of interactions for forming connections with nature during our interview with them. So too does Mike, who, when we asked him what he hoped for the future of Monday Creek, said he hoped to see people use it more. Mike also knew the importance of stories. Applying the watershed model to place, history, and storytelling about the region, Mike and the MCRP team invited, in the words of the MCRP newsletter Up the Creek, “watershed residents” to tell stories about the watershed—not necessarily about the creeks themselves, but always within the bounds of the Monday Creek Watershed. These storytelling efforts helped make the watershed not just an abstract and bureaucratic method of directing environmental restoration, but a meaningful place within the region.

The Mouth of Monday Creek

Mike stepped down as the Monday Creek Watershed coordinator in 2012. Nate Schlater now serves as the Watershed Program Coordinator. While the types of work have changed over the years and continues to adapt to new needs, the same goal remains; to protect Monday Creek. More information can be found at the Ohio Watersheds website and the Rural Action website.

Fieldworkers

Burton Bassett

Austin Miles