Bloody Twin Press

A Week with Brian Richards

In March 2018, three student field researchers, Luna Luo, Ana Mitchell and Molly Rideout spent part of a week getting to know and working with Brian Richards, a local Portsmouth poet and owner of his own letterpress poetry press, Bloody Twin Press. Today Brian is also a part-time English instructor at Shawnee State University and bassist in a local band, the Grave Robbers. Brian's focused life on the ridge enables him to pay minute attention to nature and his work. His ability to carve out a corner of the universe that is tailored for himself made him of particular interest in our driving question of how people make a sense of place in a time of change.

Over the course of four days we, the field researchers, split our time having extensive conversations with Brian at his yellow poplar kitchen table, taking hikes, and beginning the long process of cleaning and restoring his Bloody Twin Press print shop after a nearly twenty-year hiatus. Not only did we learn about the intricate process of letter press printing, but also the incredible stories and experiences Brian has had during his decades living on the ridge above the Upper Twin Creek.

All labor is a way for the brain to write, says Brian. He just doesn't always know he's doing it. He might not be actively forming sentences, but his brain is writing while he washes the dishes, while he walks and hauls wood. Something underneath is at work. Life on the ridge takes an attention to labor, a focus that requires a slowing down in order to survive. Focused, slow attention feels meditative in the way it draws one's attention to the present moment. Being present in a moment is to acknowledge physicality, to acknowledge place. Just as a poet is always writing poetry, so one is always creating a sense of place.

Bloody Twin Press

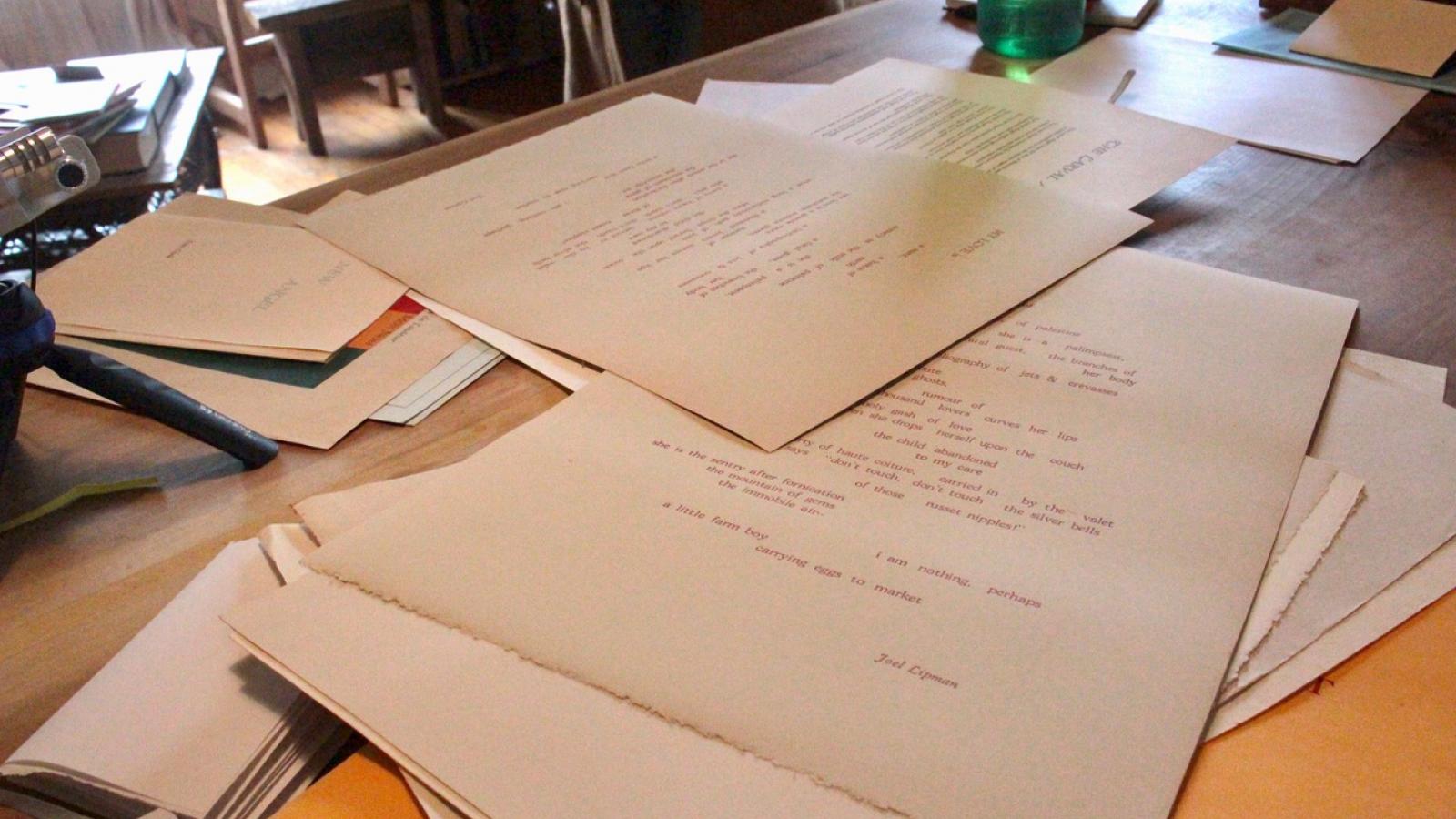

To ask why someone would use a letterpress in the age of digital printing is like asking why people continue to paint after the invention of the camera. Utilitarianism is no longer the point. Brian Richards’ attention to slow, methodical detail in the typesetting of dozens of Bloody Twin Press poetry chapbooks and broadsides is about creating artifacts that laser printing is incapable of. It has to do with touch: the raised-bump bite that the lead type leaves behind; the waxy linen of the binding thread, the pop when the sewing needle punches through the signature; the varying thickness of handmade paper that no computer can feed through. It has to do with sight: the hue of a hand-mixed ink, the bone-folded false spines, the traces of human variance. There is a crispness around each letter Brian achieves by dampening overnight the individual sheets of paper in a box he built himself expressly for this purpose. The damp, unfolded signatures are easier to bend around the Vandercook SP-20’s cylinder, easier to roll onto the type. Moist paper has more dimensionality to it, so the type bites deeper into the paper. It shrinks back as it dries and tightens the lines. This alone is a multi-day step, simply to achieve a crispness of the ink.

“I began to love more and more and more the intricate, exquisite detail of all those little steps, and it became--rather than a chore--it became part of the pleasure making the book…making those choices and taking those extra steps that would make an individual object out of it.” --Brian Richards

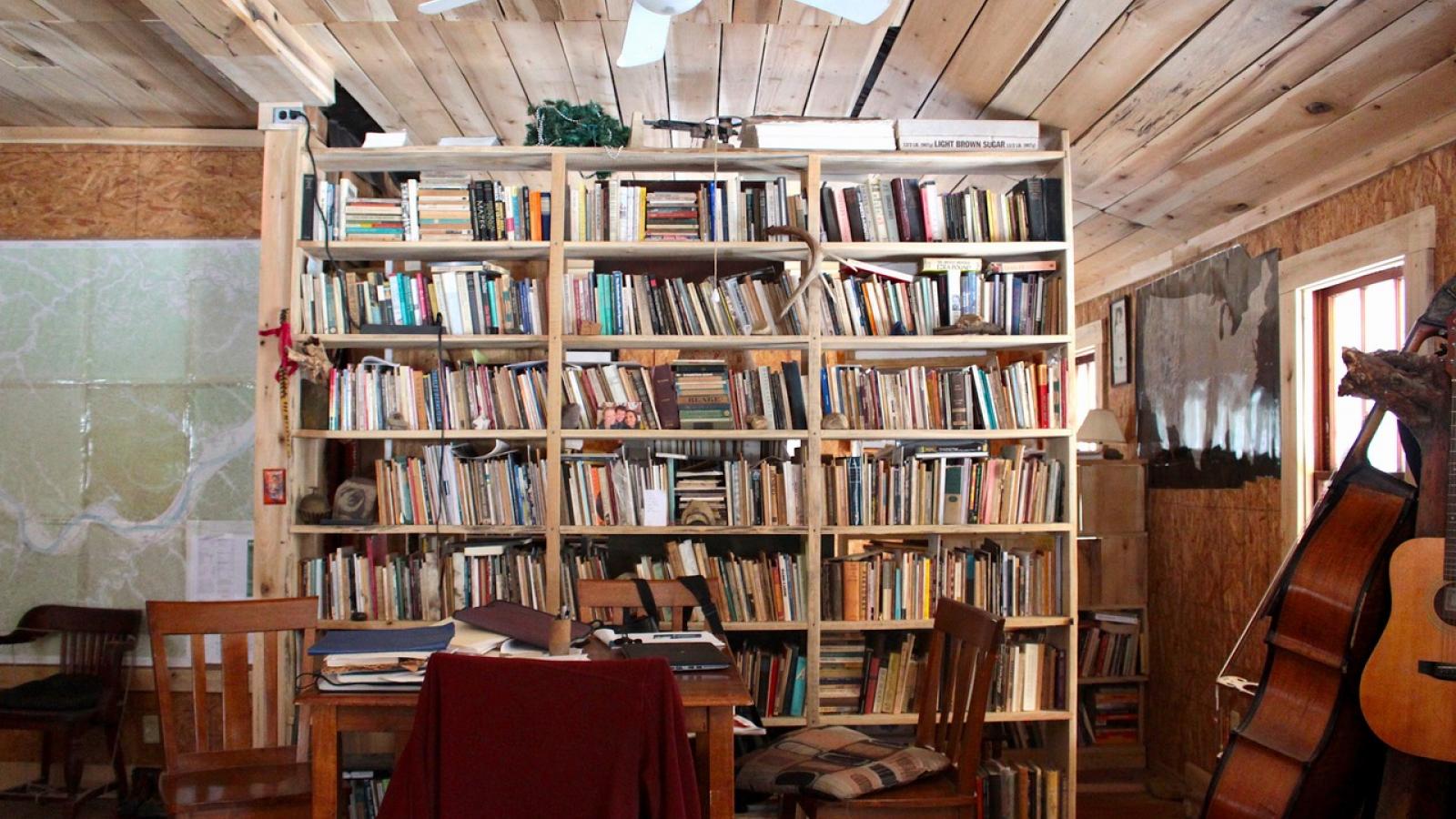

Bloody Twin Press has had different homes around Scioto and Adams County, Ohio, since its inception in 1986. Since 2000 it’s lived in a wooden shop built by Brian at the top of a ridge with more names than we can write down. He’s laid the shop out clockwise for each sequential step. First the type in their cases—the upper case and the lower case, large holdings of Baskerville 9-, 10-, 11- and 12-point font with a few larger, stranger fonts to play with for book covers. After the cases come the galley trays, onto which a completed page is assembled, the text held tight together by precise spacing, long strips of lead and magnets. Then it’s the proofing press, which needs to be hand-inked with a brayer. The imprint on the paper will be uneven, but it’s enough to check for typos or issues with spacing. He grabs the paper from the corner, a large stack of mother sheets sent straight from the supplier and next to a massive guillotine cutter that will trim off rough edges and slim the sheets to the size needed for a 4-up signature. 4-up means four pages printed on one sheet, then folded in half then half again for a four-page section of a booklet. The inks are above the counter. The Vandercook SP-20 press behind him, in the center of the room. It’s electric, the rollers self-inking. The type is transferred from the galley tray to the press. Wooden furniture of precise lengths is organized in cases under the windows. He locks the page up and a test runs begin. Brian is proud of how he’s laid out his shop. Down the counter the assembly process goes. Bloody Twin Press is about taking time with each letter of each word printed. Taking time is not the same as inefficiency.

“Choosing of the inks and the paper itself is crucial to being able to invent the book that I want to invent, and to make it be so it's a custom book. So that every step of it is not preordained. It's not something that’s standardized. It's going to be individual. It's going to represent my press and the way that I work, so that Bloody Twin Press books characteristically look like Bloody Twin Press books. And sometimes you could tell one without even having to have the name of the press on it. It would not look like it was the same as some other books are.” --Brian Richards

No one ever taught him how to do any of this, except for what he could pick up from Clifford Burke’s book Printing Poetry, which means that he had always held the composing stick wrong as he grabbed individual letters out of their cases and assembled them into words on the hand-held device. The heavy end torqued his wrist and it was hard on his thumb, but if he held it the right way the type came out upside-down and backwards. Now he knows the correct way to hold the stick. He’s looking forward to teaching his new apprentice, Kinsey Hall, how to do it right from the start.

Like much of what Brian does, there is a meditative quality in the mindful repetition this process requires. Each step of the bookmaking process takes hours, takes days. If he moves too fast then the words can come out misspelled or the lines not tight enough and the whole section will “pie.” In explaining this word, he weaves his fingers together and then opens them down toward the floor in the gesture of a day’s worth of work caving into gravity, hundreds of now nonsense letters sliding between floorboard cracks. He has container after container of pied type he hasn’t yet sorted back into the appropriate cases. Taking time saves time, Brian explains, though not in so quippy a way. Brian is not one for quips. He uses words that we have to look up in the dictionary.

Explaining the process alone takes Brian nearly two hours. Listen to his full, two-part interview that walks us through the steps from manuscript to completed book in the Ohio Field School Collection at the Folklore Archives. Local copies are also available in Scioto County at the 14th Street Community Center (c/o Drew Carter), Shawnee State University (c/o Dr. Drew Feight at the Digital History Lab), Shawnee State Park Office (c/o Jenny Richards), and Portsmouth Public Library's History and Genealogy Room (c/o Terri Stevenson).

Visit the Rare Books in Thompson Library to view editions of Bloody Twin Press’s work. (e.g. Apocalyptic Talkshow 1987, Tom Clark)

Restoring Bloody Twin Press

Even when one builds one’s life around one’s creative work, life can get in the way. It has been two decades since Bloody Twin Press has been able to print a chapbook. The shop on the ridge built for as smooth and efficient a process as possible has not yet been fully up and running. In March 2018, Ohio Field School volunteers Luna Luo, Ana Mitchell and Molly Rideout joined Brian Richards in the first steps to restoring the press. In the intervening years, mice had moved in. Paper wasps. An over-enthusiastic bush-hogger down the lane had severed the electric line leading to the building. There was rust and mildew and wood roaches to clean out. Winter clung to March 2018 and one day snow made the lane up to the shop impassible. Without electricity or heat, the lead type absorbed the cold to such a degree that our fingers went numb before the lead-dust could gray them.

The process was, like that of printing itself, one of methodical slowness, and is one that will continue on for many months to come. But as we dusted out individual trays of the California Type Case, using small paintbrushes to remove dirt and mouse refuse from compartments for each lower and upper case letter, we were able to taste, if only for a few hours, the focused care necessary for the work and life Brian has chosen for himself. There could be no dust in the type cases (dust leads to slippery letters falling out and dots in the ink on the paper), nor rust on the letters. The first day of cleaning, Richards told us stories and explained individual parts of the process. He brought out the box he built for dampening the paper, and under the heavy weight meant to hold the paper down and prevent it from becoming wavy, we found covers from former Bloody Twin books. He told us about the poets of these books and where they were now. On the second day of cleaning, the day we put aside the brooms and trash bags and began to tackle the type cases, Brian kept more quiet. All of our attention was on the methodical tasks before us. We took the type case trays out and propped them up on the open gate of the truck, an attempt to let our skin and the bitterly cold lead type absorb some of the sun’s spring heat. In an afternoon we completed only the easiest two of a few dozen trays. To us if felt like an overwhelming task, like building a shop by hand on the top of a ridge, like setting type, like testing and retesting and printing and cutting and folding and binding a 32-page poetry chapbook by hand. Like everything Brian Richards does.

Life on The Ridge

Life on the ridge above Upper Twin Creek calls for a slowness that many of us Columbus-folk are not quite oriented to. Without water, gas, or electricity, much of the tasks that one can usually complete with a turn of a dial or a press of a button must be done manually. Brian's former home on the ridge and the print shop were both built from scratch by Brian, with some help from his friend Tom Bridwell. Although this is a very laborious and gradual process, the ability to start from nothing laid the foundation for Brian to construct a print shop that was best suited to the physical process of running it.

Although Brian no longer lives on the ridge, which means he now has running water and electricity, he still has to haul and split wood to heat his house. Many of the structures within his house he built from hand: a yellow poplar dining table, a wooden bookshelf, a desiccated dogwood trunk that holds the neck of his bass and guitar. He keeps minimal broadband Internet, only allowing himself every once in a while to stream a song he would like to revisit. No TV. Brian's life inside his home reflects much of his surrounding environment- one of minimal material distraction and natural inspiration.

Life on the ridge is one of regular labor. The ridge didn't come prehoused and furnished. It took Brian time, patience, resources, and physical labor to make the ridge a habitable home. Over a dinner with Brian and his new neighbors, Kinsey Hall and Ryan Sprinkle—who now live in his former cabin on the ridge and who hope to one day apprentice with Brian in his print shop next door—the three spoke about the difficulty and precariousness of maintaining the dirt lane up the ridge. They spoke of using a pick axe and having to regularly remove any of the roots and grooves to keep path uniform. Kinsey and Ryan explained that it is such a physically demanding, yet essential, job that various friends who have offered to help in the past don’t offer to help again. There isn't any sort of quick fix; it takes time and grave attention to detail.

"Living on the ridge comes with challenges, there's no denying that, but I've found myself becoming a stronger person (both physically and mentally) since making the move there three years ago. I feel that the "tougher" aspects of ridge-life have transferred over in the way that I live my life outside of being there (my online shop, social media, day-job). It's very refreshing to return to the cabin every evening and have the opportunity to surround yourself with real-life, tangible tasks. Overall, the ridge has taught me how to be present in everything that I do, which will (hopefully!) soon include working at the letterpress." --Kinsey Hall

Later during our week, while driving down the ridge, Brian pointed to a very prominent tire track worn into the slope. He said that driving down the ridge during the winter required complete control, and any slip or skid could be a matter of life and death. Therefore, he had grown accustomed to driving as close to the side of the ridge to prevent himself from falling off. We experienced this first hand on our first evening on Upper Twin Creek. Ryan drove us down the ridge right as a snowstorm hit. He maneuvered the truck, inch by inch, down the driveway. Going slow is the only option if you want to stay alive.

The Fieldworker Experience

A personal perspective by Luna Luo

The past week living in the mountains really gave me time to reflect on myself. I used to love writing poems and reading for fun, but recently I haven't had any time to do that for fun. I still do read and write a lot, but I only do it for class, rather than for myself. I realized that the reason why I am not motivated to write as much and as well as I used to is that I haven’t read poems or novels for a long time. I am not getting the input that I need to be able to output as much. Similar to my experience, the other two women on my team, Molly and Ana, both treasured the time they had every night to be able to write field notes and reflect on their daily experiences. They think they were able to slow down their life pace by doing that. This makes me think how Brian is creating a sense of space for himself by slowing down his pace and living a life in the woods, away from the busyness of a city and the trivial gossip in a town. He's devoted his life to his poetry writing and letter press printing. It is crucial for him, as a poet, to have the time to reflect on life and to live in the present moment, rather than be destructed by all the news online, social media and all these endless things that are going on in the world. Just like for me personally, I really enjoyed how living in the woods allow me to set sometime every day to cook a small meal for myself and my team. I think it’s interesting how we often talk about time-space but don't usually perceive the world in that way. Through Brian, I realized the way one is able to create a sense of space in a changing environment is just by having a slower living pace than the rest of the world he is part of.

Fieldworkers

Luna Luo

Ana Mitchell

Molly Rideout