Working Tour with Josh Deemer in Nature Preserves

What is the role of the preserve manager? We two student field researchers, Frank Isabelle III and Dr. Anping Luo, spent three days in March 2018 with the ODNR preserve manager Josh Deemer traveling throughout southern Ohio as part of the Ohio Field School Initiative at the Ohio State University. Each morning, Josh pulled up to our cabin in his black GMC pick-up, and drove us out to different sites in need of attention. During our trip, we spent time in four different counties working in Scioto Brush Creek, Chaparral Prairie, Lake Katherine and Miller Sanctuary state nature preserves. While walking through the preserves, which Josh dubs "living museums", Josh and his colleagues taught us the ins and outs of preservation, from dumpsite cleanup and trail maintenance, to managing invasive species and other pests, all the while sharing with us the history and lore of the land.

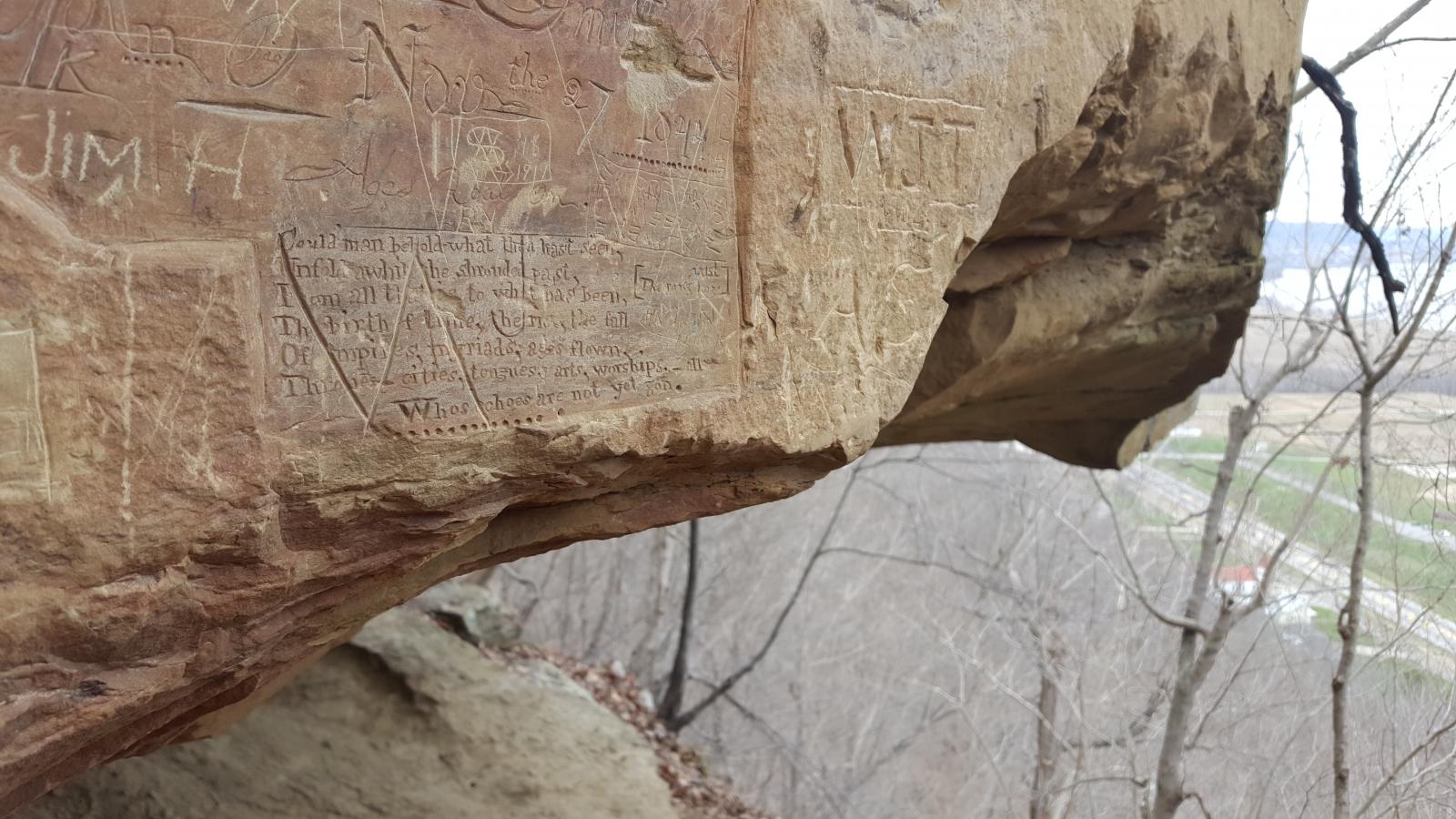

Living Museum

In early March, severe flooding overwhelmed many parts of southern Ohio. On our first day with Josh, we drove up to Scioto Brush Creek in order to clean up some of the damage caused by the flooding. At the creek, we met Matt Taylor, Josh's colleague who was busy sawing off trees that had fallen in the path. We joined him at once and began to help clear the trail. Our harvest included several plastic bags, a tire, some styrofoam, a sofa cushion, and a laundry bin.

Walking along the trail, garbage in tow, the sunlight danced through the canopy as we gazed at the wildflowers blossoming along the crystal-clear creek. As we walked, Josh identified each of the flower buds poking up through the sandy soil. “In a few weeks, this place will be loaded with flowers. You can’t imagine how beautiful it will be.” Josh says.

Further up the path, we encounter an old tree along the creek with initials carved into its trunk. Josh tells us that he tries not to get dismayed and narrates a story about a time he found seventeen trash bags full of burned rubbish. He was so upset he went through each individual trash bag all the way up to the seventeenth where he found a seared paper ball. Cracking open the ball, he discovered a few yellowed envelops full of mail. Gotcha!

“Why are you so invested in preservation?” we ask.

"Well, it’s helpful to think of nature preserves like a living museum. My job is to protect our natural heritage, and to help others appreciate it as much as I do. Sharing my love of nature with others is what makes my job meaningful.” Josh says.

Invasive Species

Josh is wearing a navy-blue jacket emblazoned with the ODNR logo, a pair of muddy gloves in hand. When he surveys the hills and valleys under his care, his sharp eyes are like those of a hunter. However, Josh is no ordinary hunter—his prey: invasive species. He bends over and pulls out a shrub, "See this? This is privet. Its roots are yellow," Josh explains as he hangs his trophy on the branches of a nearby tree, "you can't put them back in the dirt because they will re-root and continue to spread, so we hang them up off the ground in order to let them dry out.”

Later in the week, Cassie Patterson, the Director of the Folklore Archives, will join us at Miller Nature Sanctuary in Highland County as we cut, pull, and weed our way through a patch of multi-flora rose. After ten minutes pass, all of our romantic ideas about life in the woods evaporate as we quickly realize the amount of labour involved in preservation work. “That’s why we need a lot of volunteers”, Josh says. In addition to pulling invasive species by hand, Josh employs a number of other methods, such as pesticides, and controlled burns when the conditions are appropriate.

At Josh’s office in Chaparral Prairie State Nature Preserve, there is a whiteboard which lists the various invasive species in each of the eleven nature preserves in the ODNR’s southeastern district which Josh manages. For instance, Scioto Brush Creek is suffering from multi flora rose, Japanese stilt grass, Privet shrub, and Amur honeysuckle, while Lake Katherine has a garlic mustard, autumn olives, Chinese yams, etc. The life of a preserve manager is non-stop activity.

Sense of place

On the next day, we set out for Lake Katharine Nature Preserve, a 2,019-acre complex of steep sandstone bluffs, deep ravines and low-lying marshland branching off the principal lake. Up on the ridgeline, towering Hemlocks and Virginia pines loom overhead as we walk along the trail. In addition to his official role as a naturalist, Josh is also a font of local folklore. Rounding a turn, we pass the ruins of an old cabin, known as “liar’s lodge.” It’s said that this secluded retreat was built by a local man, unbeknownst to his wife, for weekend trysts with his lover. Throughout our trip, Josh brought the landscape to life with his colorful illustrations of life in southern Ohio. Naturally, we made sure to reciprocate, and Josh was more than happy to learn about our lives and experiences from Columbus to China.

For Josh, Scioto County is more than just a place where he eats, sleeps, and works. His family arrived in southern Ohio in the late 1800s, and he has no plans of leaving. With six children, Josh is always looking towards the future, and despite the drugs and poverty which Appalachia has come to be associated with, Josh loves his hometown. The city life just can’t compare. Living out in the countryside, the deep sense of rootedness and the pace of live give Appalachians a unique sense of perspective—or as Josh puts it: “We see the rat race.”

Who are we? Where will we go?

A few thoughts by Anping Luo

The most adventurous day in the field school project was when Josh and his botanist friend Rick Gardner took us on a hike at Lake Katharine to measure a potential state record yellow birch. Although the tree didn’t come near to breaking any records, I was struck by the unique and impressive Appalachian landscape.

The forest was very diverse, with several expansive caves and deep ravines. Delicate icicles dangled in the cold, contrasting sharply with the grotesque shapes of the naked trees trunks and branches. Fallen leaves piled up on the ground like a thick, soft carpet covered in an early spring snow. When treading on the yellow leaves and white snow, I felt like writing a poem, and indeed Frank is a poet! But as I watched the footprints of us four---Josh, Rick, Frank and me, I suddenly recalled one poem by Su Shi, an 11th century poet from the Song Dynasty:

人生到处知何似,应似飞鸿踏雪泥。

泥上偶然留指爪,鸿飞那复计东西.

How should one roam about in life?

It should be as a wild goose treading on snowy soil,

Its claw marks left without a thought,

As it flies east and west,

Uncaring about what was left below.

Indeed, we four strangers from east and west met without a care, leaving what behind with each other? We four just passing by in the forest – does the forest care about who we are, where we are from? And where we will go?

Fieldworkers

Frank Isabelle III

Dr. Anping Luo