Tender Letters II: Digitizing Early 20th Century Correspondence

Benjamin Beachy (History/Linguistics) and Lily Goettler (Comparative Studies) spent the 2019-2020 academic year serving as Archival Interns for the Center for Folklore Studies (CFS) during which they furthered the Tender Letters digitization project that was initiated by Ashley Clark and Emily Hardick for their spring 2019 Ohio Field School service-learning project. Dr. Barb Bradbury (Hurricane Run Farm) supervised both projects (as well as the Brabdury Farm Books digitization project from the 2018 Ohio Field School) and generously provided access to correspondence that took place between Jacob and Lenora Lapp between 1913-1915.

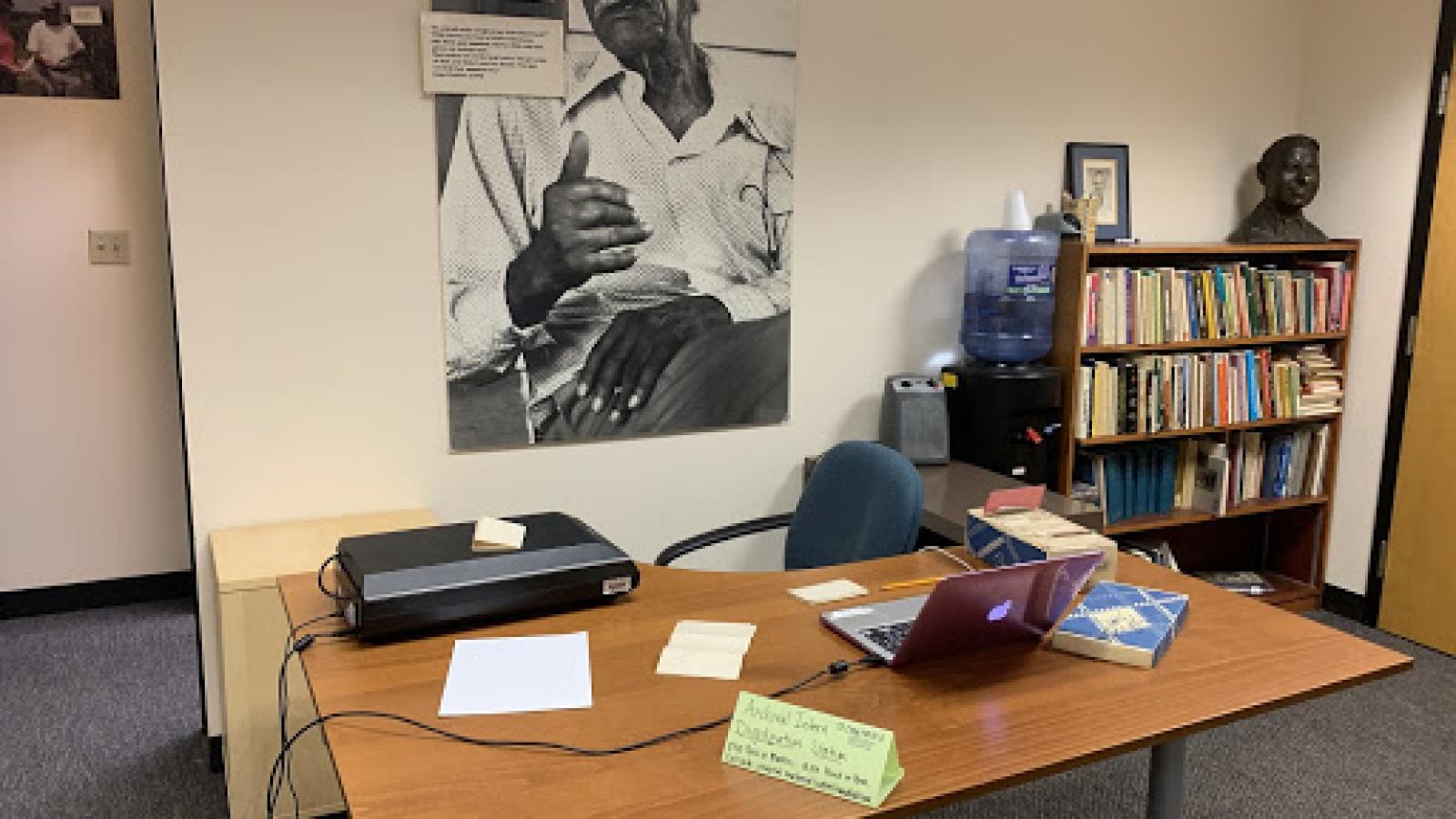

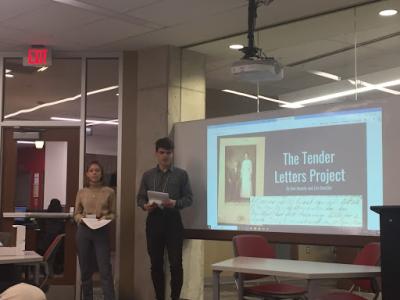

The photographs provided above are images Ben and Lily used for their presentation at the 2020 Ohio State University-Indiana University Folklore Student Association conference, which took place at the Research Commons at OSU.

The Tender Letters Project by Benjamin Beachy & Lily Goettler

Together, we’ve spent the last few months at the Center for Folklore Studies working on the Tender Letters Project, or what the subjects of our project thought might one-day be called the “Piketon Hills Romance.” With the help of Dr. Cassie Rosita Patterson and some of the other folklorists at Ohio State, we’ve been looking to bring to life this correspondence from Appalachian Ohio, and we’re excited to talk about our experiences here today!

The Tender Letters Project represents a continuation and extension of previous work done by the Ohio Field School in Scioto County with Barb Bradbury’s historical family collections. Initially in 2018, students from the Field School focused on the farm books of Barb and her grandmother, Lenora Hammond Lapp. However, the focus of the Tender Letters Project is primarily on Barb’s extensive collection of letters exchanged between her grandparents, Lenora and Jacob Lapp, before their marriage in 1915. The bulk of this correspondence lasts from early 1913 up to that point, with letters, cards, and other mementos typically being sent every three to five days.

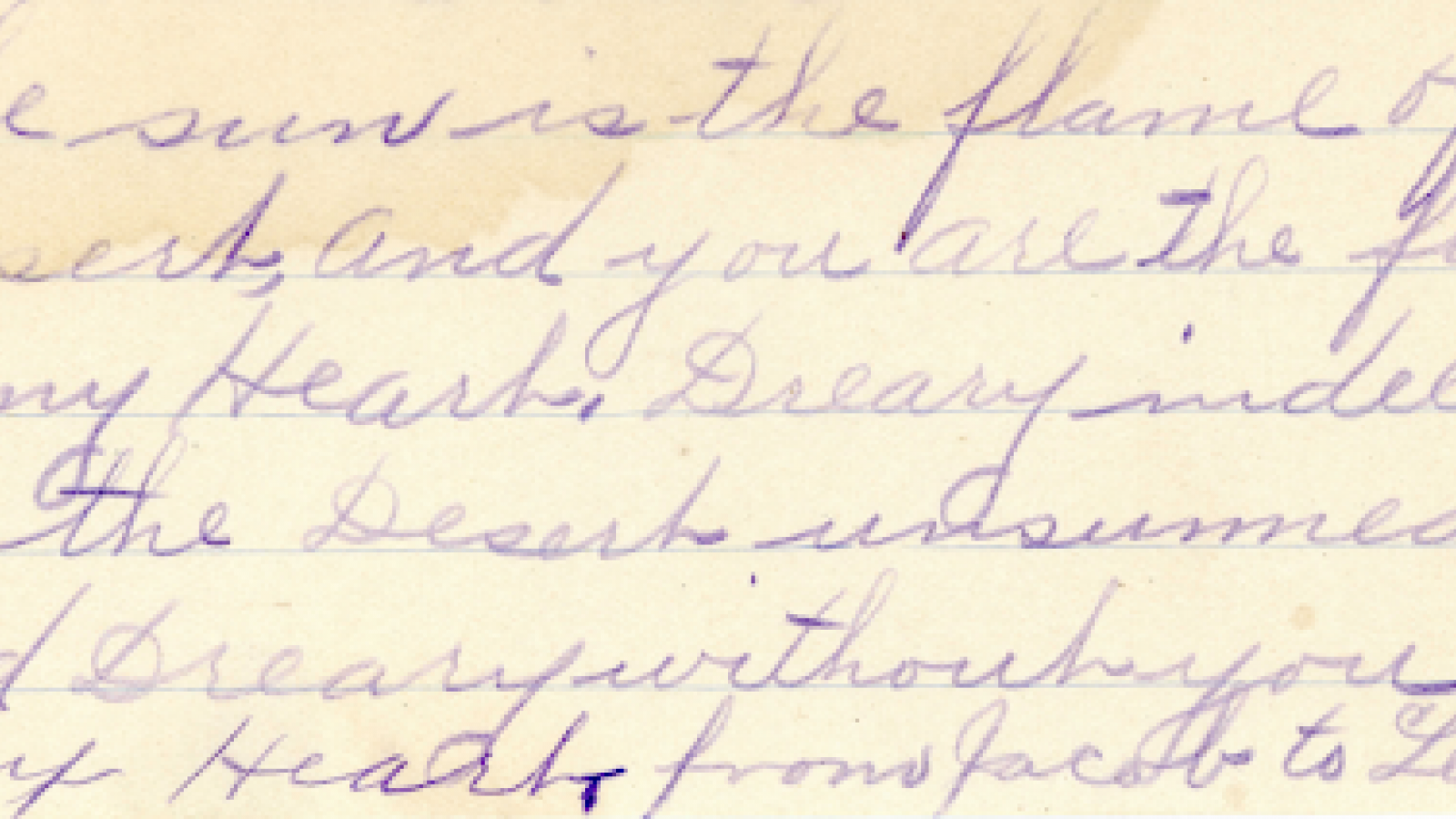

But something we’ve both noticed is the nature of their relationship. Their relationship feels very loving and warmhearted and this became obvious to us very quickly. The letters are filled with sweet poems, inside jokes, reminiscing, banter, secret codes, and special loving sign-offs -- Jacob almost always signs his letters with "Bye Bye My Darling and Goodnight." The letters never feel impersonal and stilted, it genuinely sounds like two lovers.

And along with just the very touching nature of their relationship, during our time digitizing and transcribing this correspondence, we’ve observed several different typically under-acknowledged voices emerging in Scioto County, especially related to who ends up having the agency to tell their own stories and histories in Appalachian Ohio at the time.

As Jacob and Lenora’s story is very much defined by its setting in rural Ohio in the 1910s, some brief historical context would probably be helpful! After emigrating from Germany in the late 19th century, the Lapps settled in what Jacob calls “the nicest place on earth,” the hills around Piketon, Ohio. Since that time they’ve continuously lived in the area as farmers, local civic leaders, and valued members of their communities. Lenora Hammond was originally Jacob Lapp’s schoolteacher after she stayed with his family for a brief time when she was 17. They met again in 1913, fell in love, and began a touching and well-archived correspondence shortly after, preserved by their son’s wife Zelma Riley Lapp. This tradition was carried on by her daughter and CFS Community partner, Barb Bradbury.

Today, Barb and her husband Kevin carry on the traditions started by her grandparents in several ways. After Lenora and Jacob married, they began farming just northwest of Chillicothe in Ross County. The hand-written farm logs kept by Lenora were the first subjects of the CFS’ archival efforts, and for good reason. These farm books mark the intersection of business and community life on their family-run farm. Decades-long customers, grocer connections, church and farming organizations--all of these affiliations can be found within the pages of the Lapp farm books. We can get a sense of their community network by examining the accounts, delivery schedules, and directions Lenora made note of from their day-to-day business practice.

Today, Barb and Kevin still farm with a focus on ecological care and observance in their small family farm near Shawnee State Forest. While Hurricane Run Farms generates different kinds of produce than the original farm, Barb continues to use log books that are wonderful community artifacts. The Lapp’s commitment to taking an educational role in their community, as well as preserving a caring relationship with the environment and the land is something the Bradburys keep alive and well today.

In this context of a wonderful family history in Scioto and Ross Counties, as well as the Bradburys’ proximity to so much other ethnographic and folklore work conducted by CFS and other community partners, helping to preserve the Tender Letters and bring some more continuity to their story was too good of a chance to pass up.

So, all of these things considered, Lily and I initially saw this project at the Folklore Archives as a really valuable opportunity to get our feet wet not only with folklore and ethnographic studies, but also in a more practical sense a chance to get some experience with the physical side of archiving and preservation, especially with fragile materials. By this point, six months after beginning, I think the project has become something much more personal and based on our relationship with the Bradburys, but we would like to speak briefly about that more practical side of things.

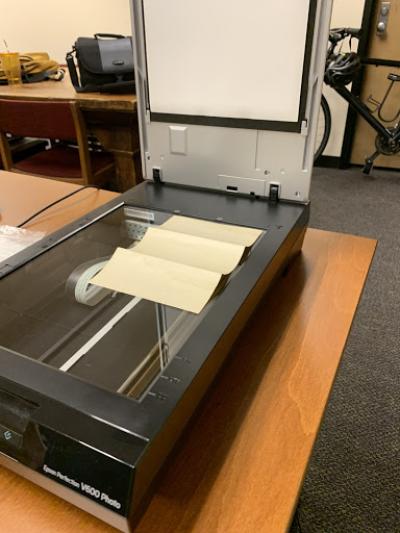

Digitizing the Tender Letters

Our digitization process began, of course, with scanning letters at the Archives! We initially picked up one shoebox-worth of letters during our first visit to Hurricane Run Farms. Immediately after this initial contact with Barb we were amazed with her and Kevin’s warmth and excitement about the project, as well as the work Barb had independently done with the material. We generally expected that to last us most of the upcoming academic year. But we quickly got the archiving bug once we really started to spend time at the Folklore Archives scanning and getting involved with the social life at CFS. Based on this excitement and the encouragement of our fellow folklorists, Ben and I really started to think about ways we could expand this project past just preserving the correspondence. We were immediately hooked by Barb and her passion for her family history, and giving the Tender Letters as much life as possible just seemed like the logical next step.

So, a few weeks in, we started talking and we decided that transcribing the letters was our “next step,” with a tentative end goal of making some sort of optical character recognition enabled searchable bank that Barb and we agreed could potentially make a great resource for area libraries and local history researchers. Barb also hoped to use the transcriptions and annotations to help create a quilt related to her own family history. And the point at which we began transcribing and really starting to bring out the voices and personalities of Lenora and Jacob, was when we just completely fell in love with the project. As we discussed earlier, the relationship between Jacob and Lenora was one that would have been unique even if it wasn’t captured by the Tender Letters, and at this point we were hooked.

Background & Contextual Research

Beyond the process of digitizing and transcribing, Ben and I were interested in doing some research that could provide some additional historical context. We were able to find extensive information of the railway system and the process of mailing in the early 1900s. The rural free delivery mail system -- began in 1896. Prior to rural free delivery, it was often hard for many rural communities to send and receive mail. We located Dove and some of the other points from which Jacob and Lenora corresponded using internet search engines and digging into genealogical research. We were eager to share the progress and work that has been done with both the farm books and the letters with more extended members of Barb’s family.

Additionally, we were really interested in the artifacts that are mentioned in many of the letters and have been working to match the physical artifact with the letters they are mentioned, such as an engraved bracelet that was mentioned in one of Jacob and Lenora's exchanges.

As we initially approached the later stages of our Tender Letters project, we only had a vague idea of what our final product was going to look like. With our main goal being to create an accessible and lasting corpus of letters and accompanying artifacts for Barb and her family, we knew some sort of digital collection was the end goal. However, inspired by Barb and the folklorists around us at Ohio State, this idea quickly expanded into something that could also serve as a public resource for researchers and anyone else who might be interested. We think that there are numerous important lessons to be learned from these letters, which we’ll discuss later, but they’re a really important potential source of education for young people and researchers in the area. While we admittedly still don’t know what form that final product might take, Cassie and the Folklore Center have given us a start. We know we’d like to make the letters searchable, and that we’d like to connect the artifacts and historically relevant details to the letters--in doing so, we’d like to get involved somehow with the local libraries or historical societies. While it’s still open-ended at this stage, the primary goal remains to make these letters a more accessible piece of family history for the Bradburys. Along with this, we want to leave the project ready to be continued by future young folklorists.

Along with that, we’re also hoping to make another trip to the area so that we and Barb can visit some of the physical spaces that these letters came from. So while the next stage of the Tender Letters project is still unclear, thinking about that end goal has brought us to some leading questions and folklore-related insights we’d like to explore further.

Representation

These questions have taken an increasingly central role in defining the project as we think of how it will culminate. Along with these, we’ve observed several typically underrepresented groups receiving a voice in Jacob and Lenora’s Scioto County. These voices challenge some dominant conceptions of rural Appalachian life, which has prompted some really fruitful discussions for us at CFS.

In terms of the leading questions suggested by the letters, we’ve primarily noticed the extremely close-knit nature of social life in Ross County. Current events outside of the Lapps’ social circle are almost never discussed, even during the Great War. Furthermore, socialization seems to occur in a limited number of ways, mostly based around the church, regular in-home visiting with acquaintances, and importantly, organized social functions. Some of the more interesting examples we continuously came across were things like the Chillicothe Farmers Fall Festivals, Church Box Dinners, Oyster and Exercise Dinners, and picnics and excursions based around agricultural holidays and military exhibitions. All of these public events seemed to be conducted with the intent of socializing young people and introducing them to a very specific way of life. We are curious about what these letters have to say regarding the scope of social life and community in the early 1910s, especially compared to those factors in the same region today.

Being able to get a glimpse of what social life was like 100 years ago and to an extent experience it through the letters, we’ve been able to contrast it with the socialization that occurs today-- it’s often much less communal and much more individualistic-- and it has led us to question why and how these changes occurred. In my own social experiences, I particularly noticed the change from the more small but intimately-connected groups of friends to today having much larger groups with less personal connection. I’m interested if the difference in social life is primarily a result of Jacob and Lenora’s rural setting or more a product of the chronological setting in the 1910s. We’re also interested in some of the social structures that have persisted over time: primarily social webs built around the church and agricultural life, both factors reflected well in the lives of Barb and her grandmother Lenora. Something we’re getting at here is that the letters portray rural Appalachian life in Ohio as very close-knit and communally-socializing.

However, we also do have questions regarding the limits of our primary sources in the Tender Letters. Is the image of a close-knit and internally-focused rural community accurate, or does a personal correspondence between young people in love, simply not discuss news and geopolitics, as you might expect? Is Jacob and Lenora’s focus on social matters a product of rural life, or do we simply have an incomplete picture of these people from our past? It’s difficult to make any sort of definitive conclusion with only the Letters as a source, but these questions have remained central to our research all the same.

While the Tender Letters are a collection with valuable implications in the field of Folklore, they also serve a very practical role as historical primary sources. Despite the aforementioned internal view of the letters, every letter in the corpus is a slice of life in South Ohio in the 1910s. They’re full of information on the country’s rail and postal systems, social events, urban interactions, occasional local political dynamics, and huge amounts of information on agriculture and rural transportation before the more widespread proliferation of cars. For example, we see details regarding being elected as a local trustees and school board officials and the centrality of the railroad for both communication and transportation. Some examples of culture and recreation in Chillicothe in the 1910s include the opera house and other theater activity, the Farmers Festival, and community activities meant to encourage courting.

Along with this more practical historical side of things, we were often surprised by the voices that are most present in the narrative presented by the Tender Letters. In several ways, they defy a lot of expectations and stereotypes that are very prevalent in the general conception of rural people, farmers, and people from South Ohio, etc. I think if you ask an average person what someone who lives along the river is like, or maybe what communities are like deep in the hills and trees of South Ohio especially 100 years in the past, you’ll often hear the same general ideas--people might say they’re close-minded, they’re unwelcoming, the sort of incomplete image of the typical “hillbilly” that many would rather avoid. But as a primary source written by some of these people, the Tender Letters do well to counter this image. We’ll return to this idea briefly.

On a different note, we also noticed the strong presence of several female voices throughout the letters. Often in history, we see the dominant narrative of a certain time or place being determined by men and male perspectives. But the Tender Letters are an exceptional example of a family history that has been preserved and shaped by several generations of women. In Barb’s own words,

“It was really my mother. My mother [Zelma] kept everything. My mother created the albums, my mother initiated communications. It was my mom’s interest, which is why we have all the material we have.” -Barbara Bradbury

In speaking with Barb ourselves, we’ve noticed the incredible archival work performed by both her and her mother Zelma. Not only is the correspondence well-preserved after a century’s time, but the corresponding artifacts, photographs, records, and other paraphernalia are all excellently organized and ordered. Everything was kept along with detailed notes. Mementos, such as jewelry and wedding buttons, are often kept with pictures of Lenora and Jacob wearing them. Materials were organized in binders, and the Tender Letters are organized in chronological order. Barb continues the tradition begun by her mother by keeping the collection internally-coherent over time. The Tender Letters are an example of family history and folklore being enacted in their best form. Even outside of Lenora’s descendants, women have played a leading role in shaping what the Bradbury family collection can tell us. Since the beginning of the CFS’ relationship with Barb, every step taken to illuminate the Bradbury collections has been determined by female voices.

As we mentioned before, so much of history is dominated by male narratives. Having Lenora's letters creates a space for her and other women, especially in rural Ohio. Having women's stories talked about can only work to help create spaces for them in the future.

The Tender Letters serve another historical role in their treatment of rural life. In the words of Barb’s husband Kevin Bradbury,

“A lot of the value in [the letters] is that they are a truer history than what is portrayed in our history books. I think history as written tends to be this narrative of so called great men and great events instead of a history of how people lived, what life was really like… I always liked the little bits of humanity. It’s all human, very human… they traveled, they visited, they dealt with illness.” -Kevin Bradbury

As an example of what historians sometimes call “bottom-up” history, the Tender Letters counter many harmful conceptions of life and culture in rural areas. One brilliant example of this comes from Lenora’s teaching career. For several years, Lenora taught integrated classes at Slate Mills School in Ross County, nearly half a century before Brown vs. the Board of Education. While this isn’t necessarily indicative of complete cohesion in race relations in the area, it dramatically predates integration in many areas which might be traditionally held as more progressive and forward.

Portsmouth and the surrounding region has a vibrant Black history which has an unfortunate history of under-recognition in many historical narratives . So it’s encouraging that though the content of the Tender Letters doesn’t have an explicit connection to those communities, through Lenora and her work we can still draw links to the past which can be helpful in bringing forth voices that are often historically overlooked.

Even if they provide an incomplete picture of the histories of these counties, the Tender Letters do show that people in the area had a very active role in telling their own stories and preserving their own traditions. They were determined to have agency in this regard. The letters challenge dominant notions of what our history looks like, and they serve as historical sources which provoke important social questions and help to answer others.

Conclusion

It’s been incredible to us how these letters, which initially might seem like limited primary sources just discussing the private lives of these two people from the 1910s have had such far-reaching implications across several different fields. [Lily] On a much more personal level, this project allowed me to feel more connected to Ohio State and the surrounding community, I’ve loved learning how to archive and be a part of such a meaningful project. [Ben] And for me, my experience with the Folklore Center has truly given me the archiving bug. It’s solidified in my mind that archiving and working with local and public history groups is probably the work I want to pursue, whether that be with CFS or elsewhere!

So, we’ve been excited to talk about the Tender Letters project today. It's been our privilege to work with the Bradbury’s historical collections in the past few months, and as we move towards the end of our time with the project we’ve really enjoyed reflecting on it and trying to formulate some kind of final product that really reflects the value we see in these sources.

We hope to do as much as possible to make a useful collection for Barb and her historical work, as well as anyone else who might find use in what Lenora and Jacob have to tell us. Thanks to CFS, and the 20/20 Conference, and all of you for giving us this opportunity today!

Archival Interns

Benjamin Beachy

Lily Goettler

Service Project Lead

Dr. Barb Bradbury